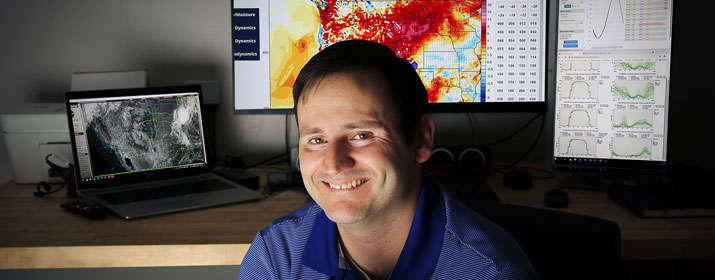

As a weathercaster for Tucson Electric Power, Patrick Lacy keeps a close eye on changing weather patterns to help us predict how much power our customers will need all year long.

Because our energy grid operates in real-time, TEP must provide the exact amount of power that customers will be using at all times. We either generate that energy in power plants or buy it from other providers on the wholesale energy market at prices that fluctuate based on supply and demand – both of which are heavily influenced by weather.

“I’m sort of a watchdog for our real-time wholesale energy traders,” explained Lacy, Energy Marketing/Forecasting Analyst. “I look at weather models 3-5 days out into the future to see if there are any impacts that might cause the load on our system to deviate from our normal pattern or energy prices to rise or fall.”

For example, storms with heavy cloud cover will diminish the renewable energy generated by our solar arrays and customers’ rooftop solar systems. This requires us to ramp up other resources to meet our customers’ energy needs.

“Renewable forecasting is something that many forecasters struggle with because resources are constantly changing, making it challenging to balance generation with load,” said Lacy, who was a weathercaster at Davis-Monthan U.S. Air Force Base prior to joining TEP a year ago. Shortly before separating from the military, he completed an internship through the Skillsbridge Program, which helps veterans transition to the civilian workforce.

Lacy develops his forecasts based on weather models created by the University of Arizona’s Department of Hydrology and Atmospheric Sciences, which uses data from the National Weather Service and the National Oceanographic Atmospheric Administration.

Cloud movement, wind direction and speed, and additional data are fed into the models to create a “microscale” model that’s regionalized for the West Coast, including Arizona and New Mexico, where our new Oso Grande Wind farm is located. “If winds are going to ramp way up or down at Oso Grande, TEP relies on solid forecasts to make actionable decisions in order to balance the grid.”

“Any weather forecast begins with the forecast funnel, starting with a look at the long wave pattern of our atmosphere’s air currents – the jet stream – and where it’s located. During monsoon, my concern shifts to the atmospheric pressure and how strong the season might be,” he said. “Using weather predictions, we can buy energy to meet our needs before prices go up.”

So what kind of weather patterns are especially troubling to Lacy and keep him up at night?

“An extended heatwave forecasted for the entire West Coast is definitely a concern when the temperatures are already 105 degrees, but what’s more worrisome is a microburst,” he said. Microbursts are powerful downdrafts or columns of sinking cooled air that produce strong winds of up to 150 miles per hour that can topple power lines and uproot fully grown trees. They’re common in Arizona during severe monsoon thunderstorms.

“You can see it in the distance and feel the temperature drop right before it hits,” he noted. “They can be life-threatening and damaging to our infrastructure.”

Lacy said he and his wife were prepared to move back to Indianapolis after they left the military. But because he enjoys his job so much and his wife also now works at TEP, they decided to put down roots here.

“What I like most is doing what I can to help our team make smart decisions. Coming from the Air Force, I learned servant leadership and becoming a leader in my own realm with the skills set and knowledge I have,” he said. “I enjoy what I’m doing and it’s exciting to learn about power generation and transmission and how it’s interconnected.”

TEP prepares all year long for extreme weather by strengthening the resiliency of our grid. In fact, our company ranks in the top quartile of all electric utilities across the country for service reliability. Our most recent scores reflect 99.99 percent reliability. Over the last four years, we reduced the average duration of customer outages from 65 minutes in 2017 to 48 minutes in 2020, despite last year’s record heat that strained our infrastructure and resources.